The Packaging Waste Imperative: What Goes Around, Comes Around

Every morning for much of the 1930s and ‘40s, Frederick Graf rolled out of bed at 4:00 a.m. to start his 14-hour, seven-day-a-week routine.

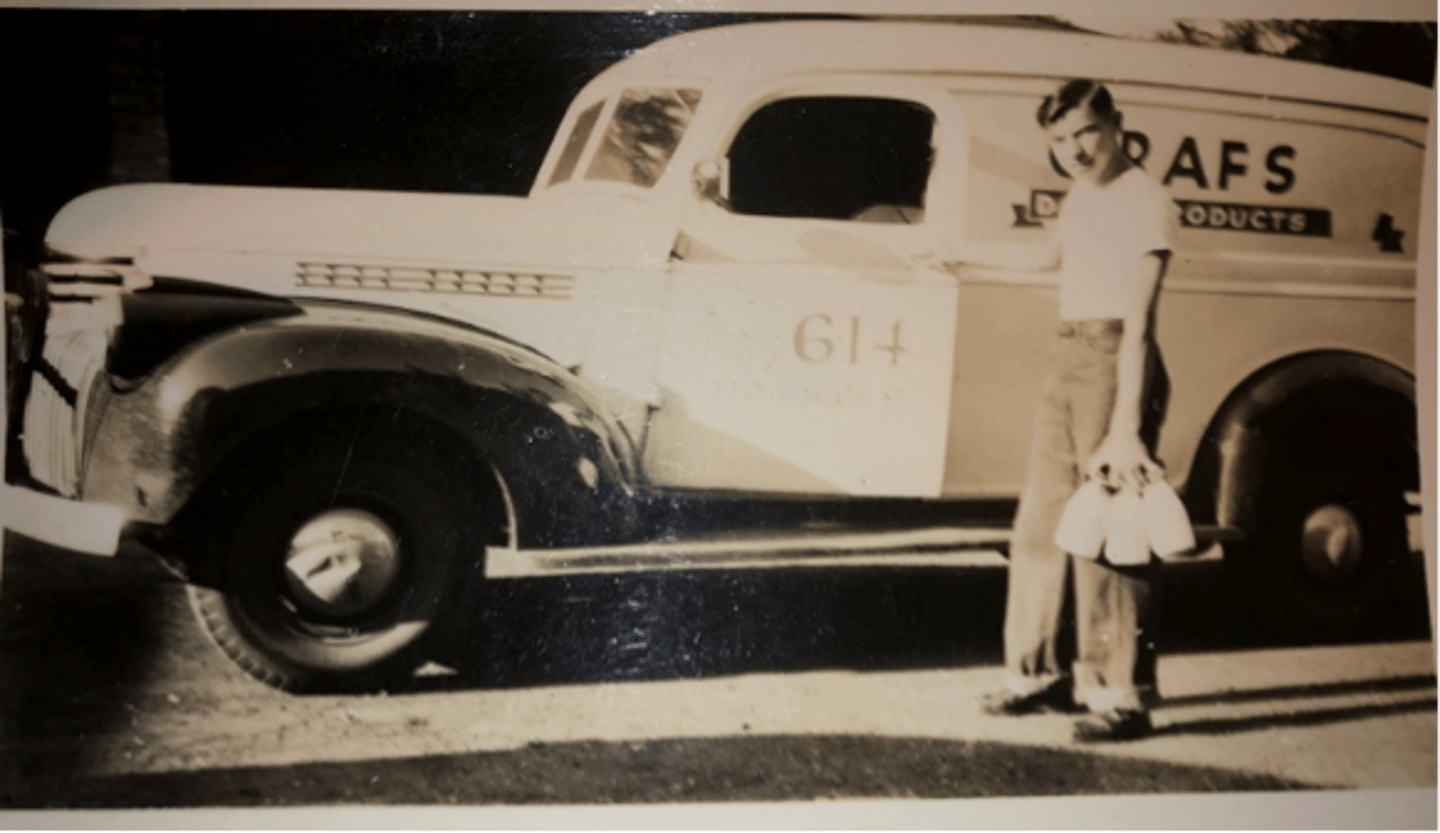

He climbed into his flatbed Chevrolet gate-truck and headed into Indiana’s rural darkness to visit the network of farmers he had befriended over the years. He delivered empty 10-gallon milk cans and loaded the cans he had delivered the previous day, now full of fresh milk.

At around 6:00 am, he returned to his dairy at the intersection of North Porter and Michigan Boulevard in Michigan City, where his sons would help him empty the heavy milk cans into the pasteurizer to start the heating process. Later, after cleaning the now-empty cans, they staged them in the truck for the next morning’s run to the farms.

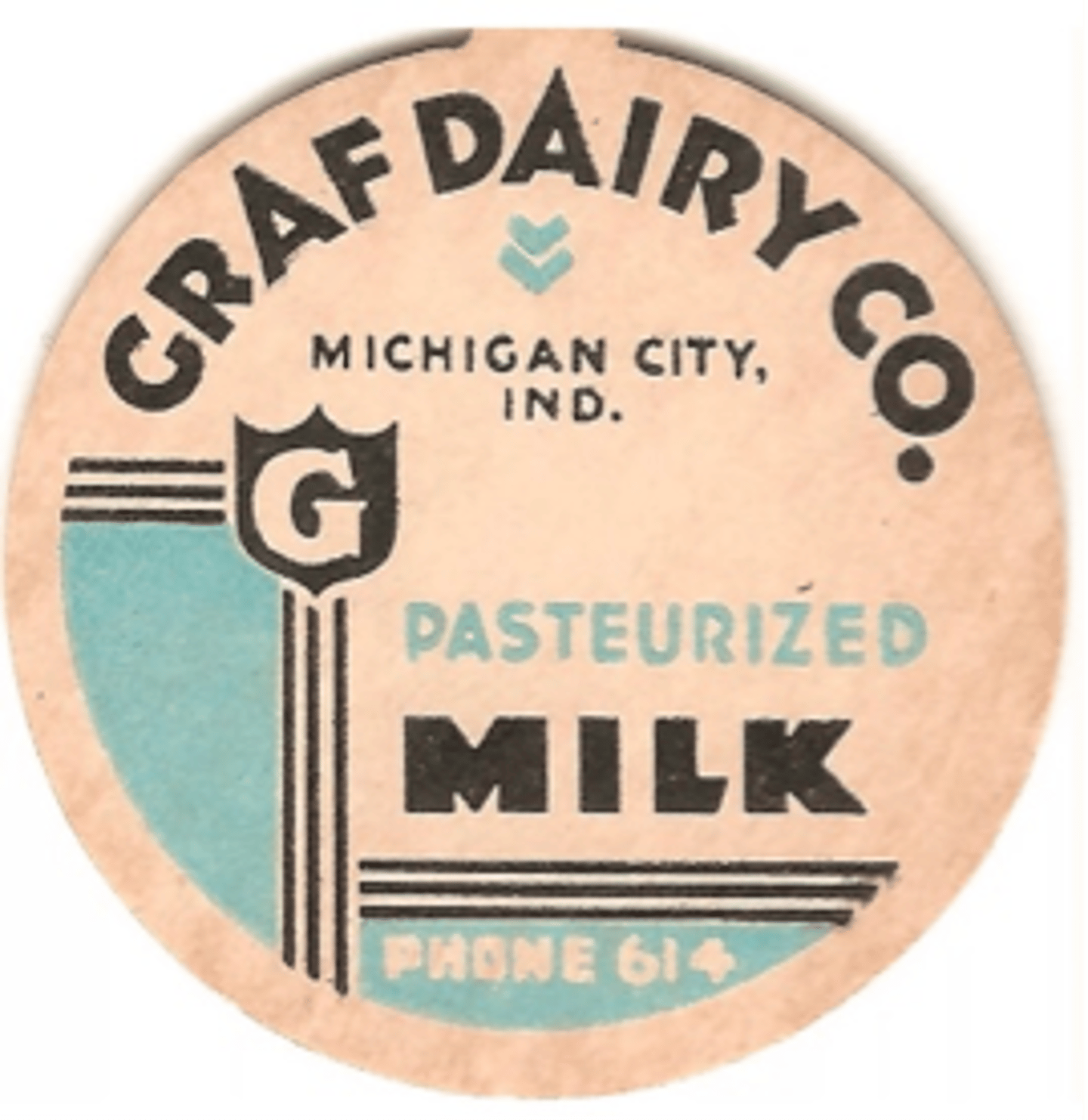

Then the fun began: Fred turned on the bottling machine, which filled individual glass bottles with fresh, pasteurized whole milk, then pressed a cardboard cap into the top and staged the inventory into the dairy’s massive refrigerator. It was a beautiful product.

Each afternoon, they would load the delivery trucks with quarts of chilled, freshly bottled milk and deliver on a strict schedule to individual homes. The Graf Dairy had three main routes, servicing mostly the German sections of town. It was a tough business, as five dairies competed for the local market. But over the years, Fred had cultivated a good reputation and a solid business. He and his sons often knew the customers by name — since they were neighbors as well as clients.

After collecting the empty milk bottles left on the porches, they returned to the dairy and spent the rest of the day sterilizing and sorting the empty bottles for the next day’s filling run. Sometimes, if not too tired, they’d make butter and ice cream for themselves with a little excess inventory before calling it a day.

Dairies of this era were tough, capital intensive, and vertically integrated enterprises. They depended on a closed-loop inventory of metal milk cans, glass bottles and strong backs (a full milk can weighed nearly 100 pounds). Given that widespread adoption of refrigerators didn’t take place until the late 1940s, the dairy business demanded not only direct-to-consumer intimacy, but a just-in-time logistics network to rotate inventory and ensure minimal spoilage. It was a lot of work, but it paid the bills and was a key service to the community, especially through the war years.

The neighborhood dairy model was essentially a product of its times, before the advent of large grocery stores, cardboard cases, paper containers and single-use plastics. There were no chemicals, no preservatives, and no waste. In essence, the process was totally green, with 100% recycling (and organic to boot!). Many companies today proclaim themselves “green” even while 80% of the plastic they generate makes its way into landfills or, even worse, the ocean.

A scary, albeit completely unverifiable, estimate from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation is that ocean plastic will outweigh fish by 2050. On the other hand, it’s completely verifiable that much of today’s plastic packaging takes 450 to 1,000 years to decompose. The waste from today’s beverage category alone is greater than all plastic grocery bags and straws, although the latter perplexingly garners most of the negative press and political attention.

Now consider glass like that used in old milk bottles. Glass is a naturally inert material made from silica, soda ash, and limestone. Even if lost to waste, it eventually disintegrates back into sand, essentially returning to nature as a natural part of the environment.

Furthermore, glass recycling programs are available to 81% of the U.S. population, according to the Glass Packaging Institute, with little of the confusion that currently plagues plastic recycling. In fact, many of today’s glass packaging already incorporates about 35% of recycled material, with 2.4 million tons of glass recycled annually into new containers, per the Glass Recycling Coalition.

End of an Era

Ironically, it was the era of disposable packaging that eventually wiped out the local glass-bottle dairies. When Borden entered the “Michiana” (Michigan-Indiana) market in the late 1940s, it presented consumers with an improved convenience: the paper carton. Polyethylene had been introduced as a waterproofing material in 1940 and, by 1968, more than 70% of milk packaged in the U.S. went into paper cartons. The milk carton machine cost more than the entire inventory of metal cans and glass bottles used by a small dairy, about $25,000 at the time (more than $260,000 today when adjusted for inflation).

While larger companies could easily make the investment, small dairies often couldn’t justify it based on their book of business. This was the case with Fred’s business, and so Graf Dairy eventually sold out to Scholl’s Dairy across town. (The Scholl’s, by the way, were part of the extended family of another iconic consumer goods company: Dr. Scholl’s. Yes, Dr. William Scholl was a real person.)

Surprisingly, Scholl’s Dairy lasted until 1963, when it finally stopped producing milk to focus strictly on delivery and distribution for other, larger producers. In a 2015 interview, Steven Scholl noted accurately: "You can't run a plant and bottle 2,000 gallons a day and compete against plants that bottle 100,000 gallons a day. The economics aren't there.”

Indeed, the modern age of grocery packaging has driven tremendous convenience for the consumer and far more favorable scale economics than the old closed-loop dairy model could have ever hoped to achieve. Concurrently, refrigeration increased shelf life and greatly reduced product spoilage. Plastics, being lighter, have also allowed for much more product to be shipped per truckload, greatly reducing fuel consumption throughout the supply chain over the years.

Such technology innovations in packaging and the economies of scale they drive are good things, having allowed for convenience, health improvements and a higher standard of living even in the face of growing populations.

Yet with all those benefits, there has also been an undeniable cost to the environment, and one to which current generations are keenly attuned. Today’s CPGs, realizing the tectonic shift in consumer attitudes toward sustainability and particularly plastic waste, are now beginning to attack the issue with vigor.

Think about it. It’s not just milk or even the beverage category alone: Your detergent bottle, shampoo container, household cleaning products — even your deodorant — all get tossed at the end of a relatively short life. Recycling efforts are confusing and not nearly as effective as most people believe, with some studies estimating as little as 14% of plastics being recycled. In fact, the Grocery Manufacturing Association wisely picked “sustainability” (or recycling) as one of its key pillars while reorganizing this past year to become more relevant to the industry.

It’s irrational to think that we can eliminate plastic, since it provides way too many life-improving benefits. But if we can’t (and in fact shouldn’t) eliminate plastics, can the CPG industry lead the way on reuse and reduction? As noted, major stalwart companies are now beginning to do the right thing, and in the process, they’re building goodwill and “authenticity” essential for wooing Gen Zers. This generation in particular is hyper-sensitive about environmental issues and just so happens to represent the largest market the world has ever seen.

SC Johnson, for example, in February launched the industry’s first package that uses 100% recycled ocean plastic for its Windex home cleaning brand. “Ocean Plastic” bottles, as many as 8 million units, will hit retail shelves soon. The new product is one of the first consumer cleaner containers in the world made this way. (Samuel Curtis Johnson, who made SC Johnson a household name and was a self-proclaimed environmentalist as far back as the 1950s, would be proud.)

There are many more examples: Nestle phasing out all non-recyclable or hard-to-recycle plastic for all product packaging worldwide by 2025; Adidas offering shoes with soles made completely from recycled ocean plastic; Colgate-Palmolive committing to fully recyclable toothpaste tubes by 2025 — at which point, Colgate says, all of its products will be contained in 100% recyclable packaging. Praise all progress.

An especially interesting development is being spearheaded by New Jersey-based recycling company TerraCycle. At the World Economic Forum earlier this year, TerraCycle introduced a durable packaging initiative called “Loop” that recently began a U.S. trial. This service allows consumers in New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania to use steel, glass and other reusable packaging — including plastic — for their normal, everyday consumable products.

If it’s not obvious, the initiative’s name is a reference to the closed-loop inventory system typical of the old dairy business, where package waste was nearly non-existent. As it was with Fred Graf’s dairy, consumers order products (from participating manufacturers including Procter & Gamble, Clorox Co. and Unilever) that are delivered in specially designed, reusable containers. Crest mouthwash is shipped in a glass bottle and Haagen-Dazs ice cream comes in a stainless-steel container that, although not too cold to the touch, apparently keeps the product cold longer and is getting rave reviews.

Loop collects a refundable deposit (sometimes $5 to $10) that gets rebated to customers when they return the containers. And just like Fred did in the 1930s, UPS will pick up empties at no additional charge. Initially, the reclaimed containers will go to New Jersey and Pennsylvania for washing, then back to the companies’ factories for refilling. Loop is tracking the incremental costs of the system, given that durable reusable packaging initially requires more material, and the shuttling of the containers in the closed-loop system burns additional energy, fuel and labor.

As a lifelong (and perpetually fascinated) observer of consumer product trends, it is absolutely surreal to reflect on my grandfather’s old business when considering today’s marketplace.

Tom Szaky, TerraCycle’s chief executive officer, was recently quoted in Ad Age stating his goal of producing items that can be reused 100 times. Loop is “all about bringing back the milkman model, where glass bottles of milk were left on your porch, and you put the empties there to be picked up,” he explained.

“The more people who reuse containers and send them through the system — rather than producing a new container for each item — the better,” he said. “We want you to see Loop packaging 50 years from now still going around.”

Fifty years? Fred Graf would probably say, “Hold my beer.” A full 70 years after the dairy closed, his milk bottles now sell for over $100 on eBay (when you can find them).

Meanwhile, the iconic milk bottle adorning the roof of the old Scholl’s Dairy remains intact, overseeing Michigan City’s Franklin Avenue. Rusted, chipped and forgotten, it looks like a ghost lamenting a lost American era, an era dismissed long ago by throw-away packaging, preservatives and convenience.

But maybe, just maybe, it’s not dead after all. “The climate, especially over the past two years, has changed,” said Anthony Rossi, Loop’s vice president of global business development. “Consumers are demanding it.”

I guess, just like an old local dairy bottle, what goes around, comes around. Got Milk?