Sales & Marketing Report 2017: Is DTC the Future — or the Present?

Last year, we focused on fulfillment as the primary problem for product manufacturers aspiring to sell directly to the consumer. We looked not only at whether manufacturers should do DTC, but also how they would do it.

In our 2016 IDC survey, when asked about the top areas driving change in their business, the number one response from consumer goods companies was “selling directly to the consumer.” It has arrived as a game-changer, both from a consumer interaction perspective and from a capabilities perspective.

IDC conducts that survey every two years, so we’ll ask that question again in 2018. For now, we must rely on the 2016 response — but to be fair, very little seems to have changed from last year. Companies are still exploring DTC as a potential channel of significance, but we’ve not seen any major overhauling of the supply chain — at least, not yet.

What we are starting to see are established consumer goods companies looking to acquire their smaller, online competition. If you can’t build it, buy it. A good example of this was Unilever’s purchase of Dollar Shave Club (at $200 million in sales, not a small company per se). For Unilever, this move certainly was about diversifying into new consumer segments, but it was also about the ability to get hands-on experience with a direct-to-consumer model.

While the eventuality of DTC seems like a foregone conclusion (as we also noted last year), the timing and mechanics are not.

Three things seem universally true:

1) Retailers will not “go quietly into that good night” (nor should they), and the dynamics of DTC and private label will bring them into ever more direct competition with manufacturers.

2) Manufacturers, at least the vast majority of them, are not set up to go DTC. Most have optimized their businesses to sell large quantities of goods to large customers, not small quantities to consumers, and this is true for both the selling (think the sales force) and the fulfillment functions.

3) Product innovation is increasingly decentralized, meaning that the national-brand manufacturer no longer has a stranglehold on new products.

The initial data certainly supports the contention that emerging, digitally enabled competitors are better suited for overcoming direct-to-consumer challenges. Repeating the point made in the overview, it has been the long-held view of IDC that falling entry barriers will let smaller “lateral” competitors steal 10 to 15 share points from traditional players over the next five years. Historical barriers to entry (such as technology and manufacturing facilities) are now either “commodities” or available via the cloud.

But the major driver is that, as younger consumers look either for personalized products or items that appeal to their generation, smaller competitors are better positioned to be flexible, take risks and deliver those products directly to consumers’ homes.

The broader question is whether DTC is going to be a major channel for consumer goods manufacturers or not — and if so, how quickly. Retailers certainly have a head start in terms of managing DTC, with the potential to use "dark" stores as fulfillment nodes — although a seamless cross-channel experience still appears aspirational for many. Unless consumer goods manufacturers (particularly in categories that more naturally lend themselves to DTC) wish to concede the online channel to retail, they’ll need to be more proactive.

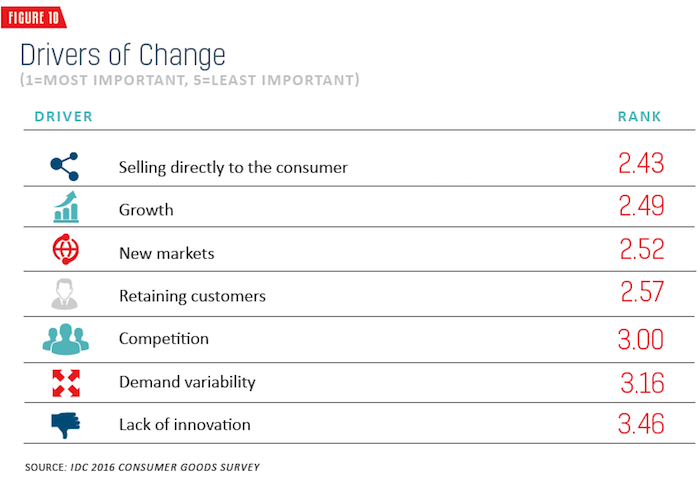

For the supply chain organization, DTC is viewed as a priority. In our 2016 survey, when manufacturers were asked about the things driving change in their business, selling directly to the consumer was the number one overall driver, as seen in Figure 10. Interestingly, growth was a close second — and new channels and markets are the best way to drive said growth. Furthermore, this was a survey of supply chain people, so it’s certainly reasonable to assume that a survey of sales or marketing people would have yielded an even higher number for DTC.

Engagements we’ve had with consumer goods companies support the contention that they are wrestling with DTC, although anytime that competition and developments are viewed as being on the fringe, the urgency for action is muted. One interesting thing here is the Amazon factor. At IDC, we tend to view Amazon more as a cloud and logistics firm — or at least that’s where we see its differentiating capabilities. Should Amazon, for example, ever decide to get into the private label/brand business in a big way, its logistical prowess would instantly make them everybody’s competition — and an unbeatable one at that. One company we’ve talked with believes that, by 2020, Amazon’s business will be split equally across online, DTC and traditional retail.

If we table the “how” for a moment and consider the “should,” the discussion becomes a bit clearer. As traditional retailers continue to struggle and close stores, the momentum behind direct-to-consumer becomes stronger.

Once the pinnacle of the department store juggernaut, Sears recently announced concern over its ability to survive. Countless other retailers have either disappeared or are a shell of their former selves: Sports Authority, Staples, RadioShack, Kmart. All of them were once dominant retail brands.

Consumers haven’t stopped buying, they’ve just moved much of their buying online, with attendant expectations for fast, even same-day, delivery. There are some product categories that favor physical retail, like grocery, but it’s an ever-dwindling number. Sure, as we already noted, a significant amount of business is done through traditional retail, but it’s shrinking fast.

So, what do the manufacturers do? They continue to support retail, certainly, but the online channel must be the future priority — through e-tailers like Amazon of course, but also through DTC.

There are other potential challenges as well. Whether it’s B-to-B or B-to-C, the essential role of logistics and fulfillment will remain the same: to deliver products and orders to customers on time and in full. But the business expectations that inform this role will change.

At IDC, we’ve been talking for a few years now about the expectations of speed and time-line compression for manufacturers in terms of order lead times and delivery speed. Forty-eight hours from order placement to shipment delivery is now the business norm in many consumer product categories, with many instances where customers and, increasingly, consumers even ask for 24 hours or less. That most distribution networks are set up with warehouse locations enabling 18- to 24-hour “drive times” suggests that expectations for speed will have a profound effect on warehouse locations and proliferation.

Furthermore, there is a strong linkage between direct-to-consumer selling and the notion of personalization that we talked about in the overview (although the latter is not exclusive to DTC). Absent a significant increase in SKU numbers and the associated challenges to the forecasting process, this suggests far more postponement requirements and a likely broadening of the key role of the warehouse.

Consumer goods manufacturers that are not yet at least thinking about modernizing their supply chains to support omnichannel fulfillment requirements should begin doing so as soon as possible. If not, they run the risk of losing market share and competitive positioning to firms that are better equipped to meet the needs of a more demanding customer.

This does not necessarily mean immediate and wholesale changes to their fulfillment networks (although it might for some consumer goods companies). It does mean evaluating and exploring the changes that may be necessary over time, and taking steps today to prepare for that future.

_____________________________________________

To read the rest of the report, click on the links below:

- Sales & Marketing Report 2017: Editor's Note

- The Progress Report

- The Evolving Role of TPM

- What to Do with Data

- Is DTC the Future — or the Present?

- Taking the Risk Out of Digitization

- Building a Smart Digital Enterprise

To download the full report, click here.