2016 Supply Chain Report

Sponsors:

Introduction

With all the attention on digital marketing and making consumer connections, the spotlight has moved away from the supply chain. However, as CGT’s third-annual Supply Chain Report reveals, there is a tremendous amount of work being done to make sure that supply chains can deliver on the new digital reality.

We once again turn to the industry’s leading supply chain experts, Simon Ellis of IDC Manufacturing Insights and Lora Cecere of Supply Chain Insights, for their views on how companies are prioritizing supply chain improvements. This year, we take a look at challenges like talent, balancing risk and resiliency, and how to extract insights from the volumes of data now available.

The outlook for the consumer goods industry remains strong, though companies are turning to their supply chain organizations to provide efficiency and productivity gains in the face of tremendous change. Is your supply chain ready?

1. Surveying the Economic Landscape

By Simon Ellis, IDC Manufacturing Insights

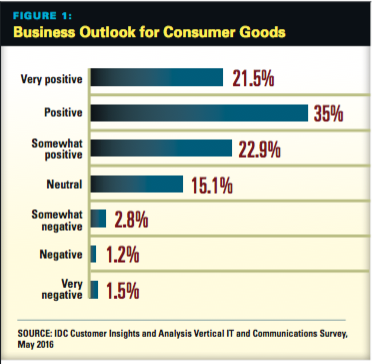

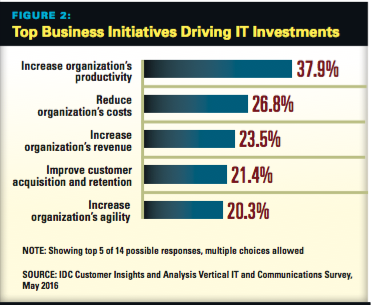

The consumer goods industry’s outlook is strong (see Figure 1), although business priorities remain more focused on efficiency and productivity, not necessarily market growth (see Figure 2).

For the industry as a whole, growth is largely keeping pace with GDP, meaning that for most regions (particularly mature regions), there is greater upside in driving productivity than in chasing small amounts of incremental growth.

That is not to say companies would turn away from growth opportunities, just that improving productivity has a bigger likely impact on the bottom line. This will have to change as long-term tepid growth will be problematic.

Further, we are already seeing competition for large, established consumer goods companies coming from unexpected places: often, smaller companies out of “left field” that are fueling rapid growth by taking market share.

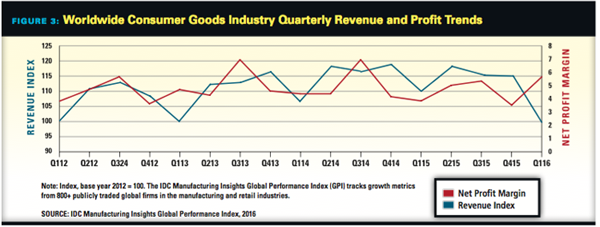

While the consumer goods manufacturing segment has seen revenues fall from this time last year, the profit margin has increased. This can be a sign that manufacturers are working toward their main IT initiatives of reducing costs and increasing productivity (see Figure 3). It also means that these businesses are seeing consumers search even more diligently for value in their purchases, with premium products suffering in the overall sales mix.

Although set in mature and established industries, consumer goods manufacturers face unprecedented changes. Traditional brand power is not enough these days, and many brands are losing their must-have status as digital-savvy consumers look to personalized products that are aligned with sustainability, safety, health and wellness. Indeed, engaging with the consumer is poised to become the single most important challenge for these businesses.

In the next decade, IDC predicts that fully 90 percent of consumer products industry growth and market share shifts will accrue to companies that engage more deeply and more effectively with consumers. In other words, consumer products companies will need to become every bit as focused on consumers as they have traditionally been on customers and products.

Management Priorities

Consumer goods companies must address the challenges mentioned in the sections that follow to achieve success in the coming years.

Continuing Pressures on New Product Development and Introduction: Omnichannel commerce, the implications of either selling or marketing directly to the consumer, and the importance of personalization and new product development remain critical to business-oriented value chain (BOVC) companies.

Leading manufacturers are complementing traditional sources of internal innovation with external sources for new ideas, including “crowdsourcing” via social media. They are also continuing efforts to streamline the innovation and new product development and introduction process.

However, increasing innovation and new products is continuing SKU proliferation, greater customization and the requirements for more diversified sales channels. Keep in mind also that much of the innovation in BOVC is to “beat the fade”, where declining SKUs need to be refreshed and replaced. As we enter the “personalization age”, this role becomes even more important.

Last, relating back to the insights in Figure 2, it’s also important to ensure that as new SKUs are added through the innovation process, poorly performing ones are removed.

The Omnichannel Consumer and Increasingly Demanding Customers: Pressures on BOVC manufacturers persist in how to manage trade promotions in an omnichannel environment, how to improve fulfillment performance and how to manage customer differentiation.

With the growth of demanding omnichannel consumers, manufacturers must be increasingly agile across channel formats and support the resulting product quality and service performance demands from their direct customers, the retailers.

Of course, the pursuit of high-growth, consumer-centric business opportunities cannot come at the expense of the “base” business, which will continue to rely heavily on traditional commerce and channels. BOVC must deliver the efficiency and effectiveness for which leading companies are known, as well as emerging capabilities to support consumer personalization and experience.

Elongated Supply Chains with Varying Degrees of Visibility: The supply side of the overall supply chain continues to elongate as manufacturers look to low-cost manufacturing for certain categories of products and profitable proximity sourcing to get closer to expanding markets in new regions.

While BOVC tends to use local or regional manufacturing more than any of the other manufacturing segments, it still experiences long lead times and a lack of both upstream and downstream visibility. Visibility is a particular challenge when manufacturing is a combination of both owned and outsourced facilities. Improving connectivity to suppliers, increasingly through B2B networks, is critical, as is the ability to see into not only Tier 1 supply but Tier 2 and 3 supplies as well.

Ongoing Challenges Connecting Supply and Demand: Elongating supply networks are “complemented” with increasingly volatile and fast demand expectations, creating a cycle time discrepancy across the two sides of the supply chain.

Using downstream data to improve forecasts helps, as does the employment of more agile inventory. But, the reality is that agility in the form of operational resiliency is critical, and many companies find themselves inadequately prepared to respond to disruptions.

Sustainability and the Assurance of Supply: Sustainability continues to be an important driver for BOVC companies, particularly as it relates to operational efficiency (consumption of energy and water, for example) and environmental stewardship.

But increasingly, companies are concerned about the “assurance of supply” and that constrained input will impact the business. Whether we call this sustainability or something else, the ability to manage the available supply is critical for continued operation and service delivery. We hear companies talking about conflict supply, buying capacity rather than volume and the tradeoffs of increasing vertical integration.

2. Supply Chain Risk and Resiliency

By Simon Ellis, IDC Manufacturing Insights

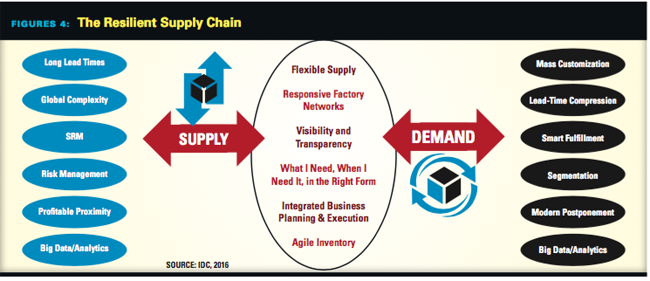

Risk and resiliency are flip sides of the same coin. To be a resilient supply chain requires that risks are clear, and comprehensive risk assessment is a critical component of resiliency (see Figure 4).

Further, resiliency is not just about proactive mitigation; it is also about reactive speed and how well a company responds to a situation — and is therefore better positioned to take advantage of limited alternatives. Every supply chain does risk assessment to some degree and considers some range of potential responses. Yet, the variability in the effectiveness of this approach varies greatly.

The manifestations of resiliency, as well as the drivers, will differ for different consumer goods companies. For some, it may be about improving inventory performance; for others, it may be about visibility into mixed factory networks; and for others still, it may be about supplier diversification.

It is also important to understand the various functional areas within typical end-user organizations that are “interested parties” when it comes to managing risk and resiliency. While the consumer goods supply chain is a vested partner, risk and resiliency is ultimately an enterprise-wide concern.

Types of Risk

It is also important to keep in mind that risks, and the ability for a supply chain to be resilient to those risks, is not just about the “big” things. While we may all be distracted by the prospects of wars or major climate events, the reality is that supply chains suffer far more in an aggregate sense from small risk: things that happen every day.

The principal point here is to recognize that not all forms of risk are long-term or “structuralized,”and that in many cases, rapid response is more appropriate than mitigation. In almost all cases, though, timely visibility into what is happening, and where, remains THE critical enabler of resiliency.

Strategic Risk

Strategic risk typically relates to policy. These are big decisions and do not lend themselves to rapid response or quick changes. Proactive mitigation is called for here:

1. What is my approach to supply? Do I take a low-cost, restrictive sourcing approach? Or, do I diversify across a network that is not narrowly dependent (either geographically or technologically)?

2. What is my logistics network strategy, and how do I engage with and qualify that network?

3. What is my inventory policy — not just the overall contribution to working capital, but how I approach different states and where I hold them?

Tactical Risk

Tactical risk is where much of the appeal can be found — those things in the business that can benefit from pre-planning, some mitigation and a significant amount of quick response. It typically relates to procedure:

1. A supplier has gone out of business. Do I consolidate into my existing supply network or bring a prequalified alternative on line?

2. How do I manage an inventory quality problem? Do I shift my warehouse footprint or repurpose work-in-process or component stock?

3. A warehouse has experienced water damage and must be closed for a month. Do I revise my network shipping procedures; arrange for overflow capacity?

Operational Risk

Operational risk is mainly about navigating the day-to-day challenges — and opportunities. It is rarely about mitigation, though preparedness is important; almost always it is about responding quickly to the many disruptions that occur daily or hourly. Operational risk typically relates to execution:

1. An unforecasted order has come in from a top customer. Do I reallocate stock from a lower priority account, divert a warehouse shipment or reply that the order cannot be filled?

2. A shipment to a customer has been delayed. Do I reroute a different shipment, provision an alternate carrier or proactively inform the customer of the delay?

3. Product has been put on quality-hold due to a potential contamination issue. Do I reallocate stock, rush the quality testing or just inform the customer of a delay?

Stages of Risk

Although there are businesses that have an identified risk officer, the majority of end-user companies share the responsibility for risk across multiple functions and business processes. It is this very fragmented nature of risk that results in so many businesses having a less mature approach to resiliency. The end result is that most companies do not have a comprehensive view of risk and are vulnerable to any number of potential disruptions.

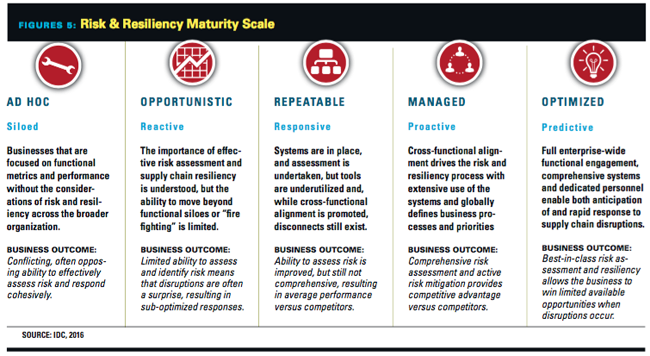

IDC has identified five distinct stages to risk and resiliency in the manufacturing supply chain as illustrated in Figure 5.

Each of the five stages has its own distinct set of characteristics and expected business outcomes, ranging from the very least mature siloed stage to the most mature predictive stage. Most of the consumer goods manufacturers that we work with are either in the reactive or responsive stage, with some moving to be proactive. Very few are as yet in the predictive stage of maturity.

3. Supply Chain Collaboration

By Simon Ellis, IDC Manufacturing Insights

As we noted in this report last year, much has been written on the subject of collaboration over the years, and two points seem to be universally true. First, better collaboration, either internally within the business or externally with suppliers or customers, invariably yields positive results. And second, when queried on the topic, companies invariably believe that their collaborative efforts can be improved.

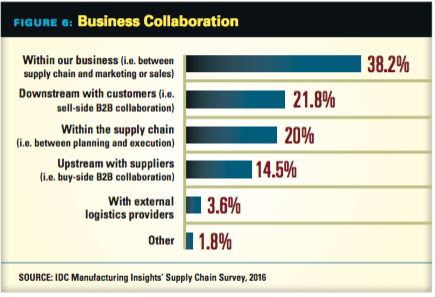

While collaborating within one’s company would seem like it ought to be easier than collaborating externally, many consumer goods businesses have rather rigid functional barriers that can make internal collaboration a challenge. Indeed, in IDC Manufacturing Insights’ 2016 Supply Chain Survey, when we asked what aspect of collaboration was a priority, the largest response was to focus on collaboration “within our business” (see Figure 6).

Further, when we asked consumer goods manufacturers about the topic of improved collaboration, four topics were top of mind:

-

Improve customer service,

-

Increase the performance of the new product development and introduction process,

-

Reduce costs, and

-

Selling to the consumer.

While the first three priorities may seem, on the surface, to be “motherhood and apple pie”, they are ultimately what will determine whether a business is successful or not. It’s the fourth one that is of particular interest and something we have been following for years. It is also something of an open question about how direct-to-consumer initiatives will work, and whether they require more effective collaboration between consumer goods companies and retailers.

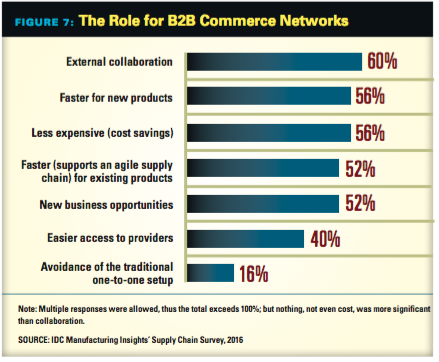

Intercompany collaboration is very important as well — particularly as consumer goods companies continue to outsource capabilities to external partners — and we see an increasingly important role for cloud-based B2B networks. At IDC, we have noted that perhaps nothing in the emerging “digital age” of the supply chain offers more promise for driving positive change than broad participation in these networks — and collaboration is a big part of what drives the benefits.

Indeed, in our 2016 survey, external collaboration was the single highest benefit that consumer goods companies have seen from their participation in networks (see Figure 7).

4. Adopting New Forms of Analytics

By Lora Cecere, Supply Chain Insights

Supply chains are drowning in data, but are low in insights. While the cost of computing memory was once a barrier to executing an analytics strategy, this is no longer the case. The greatest barrier is the understanding of new forms of analytics.

Historically, the phrase “supply chain analytics” was used to describe reporting. This is no longer the case. Today, there are more options and capabilities for supply chain analytics. There is a proliferation of new technologies flooding the market.

Why Are Analytics Important?

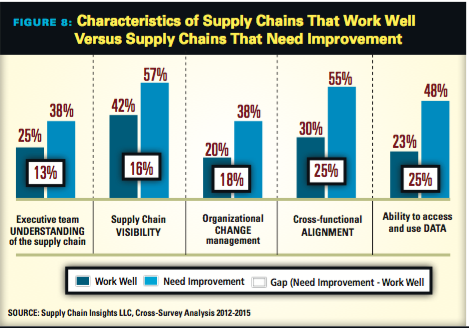

Driving change requires education, testing and experimentation. The technology market is shifting — a market evolution with promising capabilities. When we ask companies to rate supply chain performance, supply chains that work well have a significant difference in five areas. These are shown in Figure 8. Ability to use data is one of the five characteristics defining supply chain excellence.

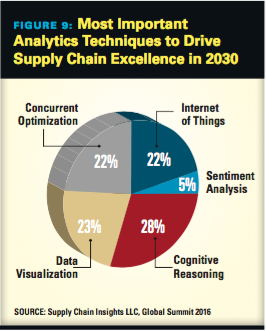

This evolution of “Supply Chain 2030” strategies will be built on multiple analytics techniques, not just one. The portfolio of analytics defining the supply chain in 2030 is shown in Figure 9. More than 75 percent of the technology portfolio for 2030 is dependent on new forms of analytics.

What Are The Barriers?

Adopting these new forms of analytics requires addressing three primary issues:

1. New forms of supply chain analytics providers have the goods, but not the knowledge. New supply chain analytics vendors are struggling to learn supply chain. They do not have supply chain backgrounds and each manufacturing/distribution organization is different. As a result, the requests coming from manufacturing companies are confusing.

2. Traditional supply chain vendors have the knowledge, but are slow to change/adapt. Traditional supply chain technology solution vendors are slow to adopt new forms of analytics. Why? It requires a re-write of traditional architectures. As a result, the adoption of supply chain analytics forces companies to redefine current standards for technology purchases.

3. New capabilities redefine supply chain fundamentals. Supply chain processes are changing. The shifts are many. New forms of analytics are redefining decision support.

The definition of an analytics strategy to drive competitive advantage requires leadership by the business team.

5. Metrics That Matter

By Lora Cecere, Supply Chain Insights

Consumer goods supply chains serve global markets. Growth agendas dominate supply chain strategies, but growth is slowing. An increase in complexity lengthened the long tail of the supply chain, adversely impacting cost and return in invested capital.

Supply Chain Performance

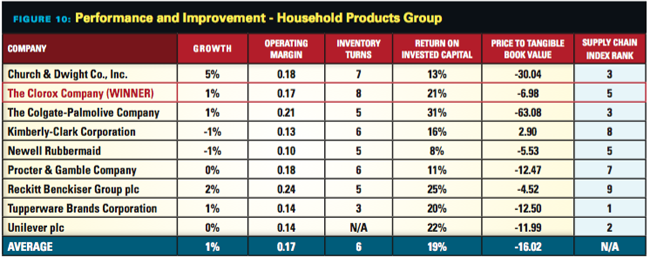

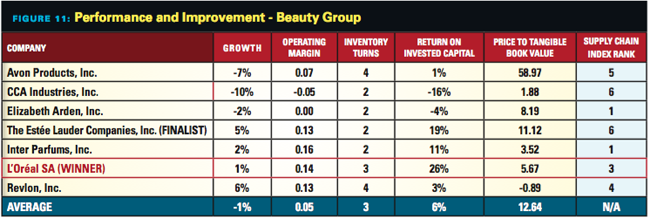

When it comes to overall supply chain performance industry averages, Figures 10 and 11 show the performance and improvement trends of the industry.

Supply chain leaders argue on which companies perform the best. We think that the data speaks for itself: Clorox and L’Oreal are winners of Supply Chains to Admire awards for 2016, while Estée Lauder is a finalist.

The stories of success have commonalities: A focus on improving customer segmentation and tailoring the supply chain response based on cost-to-serve. Each company managed item complexity and customer requests through refining cross-functional processes.

6. Supply Chain Talent

By Lora Cecere, Supply Chain Insights

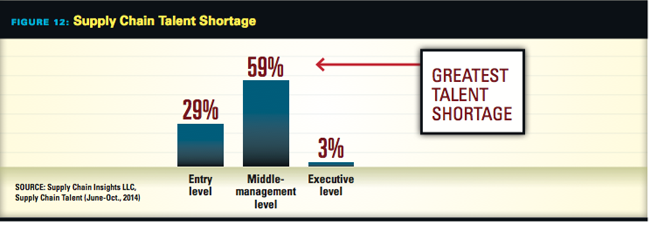

The missing link for most supply chain leaders in the race for supply chain excellence is developing and retaining talent. While most have programs for entry-level hires and executive leaders, as shown in Figure 12, the biggest gap is in the development and retention of mid-management leaders (senior managers and directors).

The reasons are many: early retirements, growth in global markets and the growing importance of supply chain leadership. The struggle is what to do. What defines success to fill this gap? Certification programs focused on historic practices are not sufficient, and the current academic programs are a better fit to build entry-level skills.

Building next-generation supply chain processes to drive higher levels of value also requires questioning the status quo and rethinking processes. Customer-centric, demand-driven, network of networks and outside-in processes will become the reality in 2030.

The supply chain of the future is no longer about cost containment. Instead, it is the engine of growth through test-and-learn capabilities, and building the right talent to embrace new ways of thinking is critical.

As you work on your strategic plans for 2017, ask your organization tough questions.

-

Are you building next generation supply chain talent?

-

Can your organization adequately discuss how you are going to build 2030 strategies?

-

Is there a clear design?

-

Are you clear on the role of analytics, robotics and the Internet of Things?

-

What does machine-to-machine automation mean for your supply chain?

-

Do your work teams have a clear vision of the skill sets required for the autonomous supply chain?

-

Do you know what the network of networks looks like for your team as a goal?

-

Or does a lack of knowledge about how to speak a new language hamper your team’s ability to embrace open source analytics? Does this also hamper the ability to rethink the current limitations of ERP architectures and the constraints of master data management?

-

Is there a need to retool? Learn a new language? And better define the supply chain that could be while identifying what this means for job progression, work teams and change management?

This is the work that lies ahead. The biggest gap is changing skill requirements.

7. The Value Proposition of S&OP

By Lora Cecere, Supply Chain Insights

What drives value in a “value network”? Progressive supply chain professionals will often wave their hands and state a goal to drive value. While the traditional supply chain leader drives a cost agenda, a more progressive leader will attempt to drive value-based strategy. This makes sense, right? Yes, I agree.

Agreement is easy until someone asks the supply chain leader to define value. Then the discussion becomes a bit sticky. The issue is defining value.

What Drives Value?

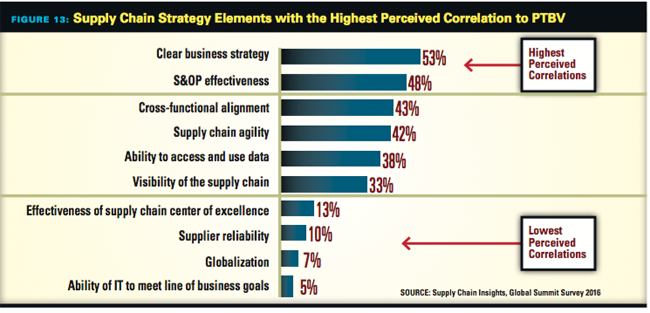

Are we clear on what drives value? The factors that 60 supply chain leaders attending a recent conference believed drove improvements in price to tangible book value (PTBV) are outlined in Figure 13.

These global leaders believe that the highest correlations were a clear business strategy, S&OP effectiveness, cross-functional alignment, agility, and the ability to access and use data. The lowest correlations were believed to be supply chain center of excellence effectiveness, supplier reliability, effectiveness of globalization and the ability of IT groups to meet business goals.

The experienced group of supply chain leaders was only partially correct. Only four factors correlate. This includes an effective S&OP process, an effective supply chain center of excellence, supply chain visibility and supplier reliability. It is interesting to note that there was no correlation to the type of technology selected or the effectiveness of IT technology strategies.

What Can We Learn?

Tie Strategy to Action. While many companies have an effective supply chain strategy, it only drives value when it is tied to execution. The effective supply chain center of excellence makes this happen.

S&OP Effectiveness Matters. Companies that rate themselves higher at S&OP are better balanced and aligned between commercial, finance and operations teams and drive higher value.

Build Effective Supplier Relationships. Supplier visibility and reliability matter. Many companies have focused on transactional efficiency and have forgotten the focus on supplier development, reliability and visibility. Basics matter. It isn’t how effective a company manages the purchase order; instead, it is about the effectiveness of managing the supplier relationships.

What is the bottom line? Supply chain leaders can drive value. Excellence no longer needs to be defined by a cost agenda.

To download a copy of the full report, click on the attachment below.